|

The Agony in the Garden |

|

One of the great delights of the National Gallery in London is the positioning of these two versions of the Agony in the Garden, side by side for easy comparison. I'll do the same here. |

|

|

|

|

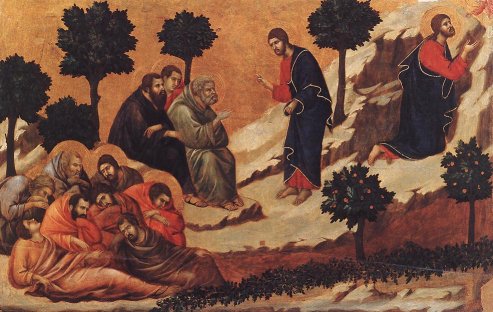

| Two

wonderful paintings - but Anna Jameson, in The History of Our Lord as

exemplified in works or art, didn't think so. In fact, both

paintings left her extremely vexed. We'll explore why below. First, to the event

itself. The synoptic gospels are generally in agreement. Here is Mark chapter 14, from verse 32. And they came to a place which was named Gethsemane: and he saith to his disciples, Sit ye here, while I shall pray. And he taketh with him Peter and James and John, and began to be sore amazed, and to be very heavy; And saith unto them, My soul is exceeding sorrowful unto death: tarry ye here, and watch. And he went forward a little, and fell on the ground, and prayed that, if it were possible, the hour might pass from him. And he said, Abba, Father, all things are possible unto thee; take away this cup from me: nevertheless not what I will, but what thou wilt. And he cometh, and findeth them sleeping, and saith unto Peter, Simon, sleepest thou? couldest not thou watch one hour? Watch ye and pray, lest ye enter into temptation. The spirit truly is ready, but the flesh is weak. And again he went away, and prayed, and spake the same words. And when he returned, he found them asleep again, (for their eyes were heavy,) neither wist they what to answer him. And he cometh the third time, and saith unto them, Sleep on now, and take your rest: it is enough, the hour is come; behold, the Son of man is betrayed into the hands of sinners. Rise up, let us go; lo, he that betrayeth me is at hand. Luke adds some detail that artists have exploited, or maybe over-exploited: And there appeared an angel unto him from heaven, strengthening him. And being in an agony he prayed more earnestly: and his sweat was as it were great drops of blood falling down to the ground. (Ch 22 v 43-44). So what annoyed Anna Jameson? The second volume of The History of Our Lord was in fact completed after Anna Jameson's death by Elizabeth Eastlake, but the comments have all of Mrs Jameson's usual asperity. Her grumbles were with perhaps the majority of Renaissance portrayals of this scene. Her first complaint was with the positioning of the disciples, which, she felt, were given a far too prominent role in most paintings, when the focus should have been on Christ himself. Here are some more paintings of the subject: is she right? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Christ is given

due prominence in the Botticelli, and the Duccio is clearly a narrative

painting showing Christ either leaving or returning to the Disciples as

well as the moment of supplication. Fra Angelico does rather dismiss him

to the background, where he floats somewhat unconvincingly above a tree.

Giovanni di Paolo manages to squeeze in all the Disciples, including the

ones Christ left behind. Mrs Jameson's more serious complaint concerns the frequently seen cup borne by the angel. Jameson points out that 'take away this cup from me' is a metaphor; 'It need hardly be observed, to the reader who has thought at all on these subjects, that the attempt to render a figure of speech through the medium of any form of art addressed only to the eye, must be always unsuccessful in interest, and often false in meaning. A metaphor in words becomes a reality in representation. Such a metaphor our Lord employed in the prayer that this cup might pass from Him. The cup, we know, is a frequent figure in the allegorical language of Scripture. There is the ‘cup of wrath’, and the ‘cup of salvation’, and there is, emphatically, ‘my cup’, of which Christ says that all his followers shall indeed drink; the very anticipation of which now caused him such anguish of mind and body.' There is a further point here; the (metaphorical) plea is 'take away this cup'; in paintings, the angels are handing one over to Christ. Jameson considers the parade of little angels even more absurd: 'In Mantegna’s Agony in the Garden - the false idea is further developed by the absence of the angel and the substitution of a whole row of little angioletti, who present all the instruments of the Passion. The cross, the column etc., together.' Here are the relevant details from the two National Gallery pictures: |

|

|

|

|

| For

similar reasons she is even more scathing of Poussin's version,

(right, below) and it is difficult to disagree with her.

Jameson goes further. She felt that

paintings such as these are not simply absurd, but positively heretical. |

|

|

|

|

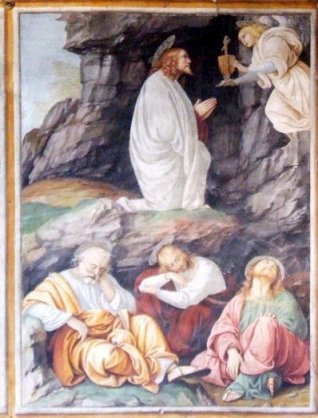

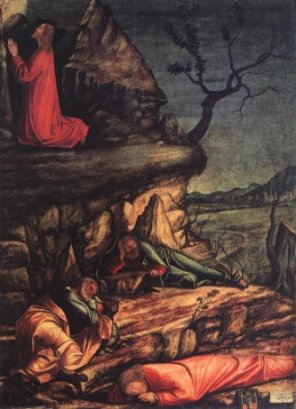

| So: let's look at some other versions, ones that might appeal to Jameson by focussing on the anguish of Christ rather than on decorative little angels. I've selected two, both from Venice. | |

|

|

|

| Carpaccio has

included the apostles, but they are discretely placed, merging with the

rocks. There are no angels, just Christ in his red robe. Basaiti

has apostles and an angel, but as far as I can see no cup. The picture

also has a touching solemnity enhanced by the bleak, rocky setting and

the thoughtful saints. So was Mrs Jameson right? Frank DeStefano (http://giorgionetempesta.blogspot.co.uk/) has kindly passed on the following quote from Church Symbolism (F. R. Webber, Cleveland 1938): 'Foremost among the symbols which have been revived today are those of our Lord’s Passion. Writers often speak of he “thirteen Passion symbols,” but in reality there are more than that. As far as we know at present writing, there is but one universally accepted symbol of the Agony in Gethsemane, seven or more of the Betrayal, seven of the Trial and Condemnation, seven or more of the Crucifixion, and about the same number of the Descent from the Cross and the Burial. The Agony in Gethsemane is almost invariably pictured by the use of a jewelled chalice out of which is rising a small cross, with pointed ends. This is called the Cross of Suffering. The chalice is golden in colour, and the cross is red. The reference, of course, is to our Saviour’s prayer in Gethsemane concerning the Cup of suffering, as recorded in St. Luke.' One other thought. In working on the next stage of the passion story, the betrayal and arrest of Christ, this quote from John's gospel leapt out at me: 'The cup which my father hath given me, shall I not drink it?' (Ch 18 v 11). This neatly counterpoints the image discussed here, and provides, in my view, a justification for its inclusion in scenes of the Agony in the Garden. So; have I changed by mind about the Mantegna and the Bellini? Well, Jameson's points are interesting ones, but I still like these pictures, and will go and gaze lovingly on them again on my next visit to the National Gallery. Both these paintings have another element, not mentioned so far; the approach of Judas and the soldiers in the background. The betrayal of Christ will be my next topic. |

|

| Passion index Home page - explore the site | |