|

Noli Me Tangere - The appearance of Christ to the Magdalen |

|

|

This scene from the events of the Passion and Resurrection of Christ is a

popular and emotionally resonant one. |

|

|

Duccio’s design is touching in its simplicity; the Magdalen as modest as she is adoring, and Christ as loving as He is divine. |

|

|

|

|

|

No commentators, ancient or modern, have ever satisfactorily explained why Jesus denied to her that touch of Himself which he proferred to those of the doubting disciple. But in art this action, ‘Touch me not’, needs no vindication. He has passed the gates of death. She is still on our side of them. He is the same, yet mysteriously changed, for mortality has put on its immortality. A narrow Space only divides them, but yet it is ‘the insuperable threshold’. and she as those ‘who stretch in the abyss the ungrasped hand.’ Art, like music, is privileged to suggest many meanings besides that prescribed. Giotto is the only painter we have seen who brings before us a wider view of the scene. It would seem as if he had read the words of St. Chrysotom, for the two angels sit solemnly at the head and foot of the tomb, within a few feet of the Magdalen, each looking and one pointing at Christ, as if they had just aroused her perception to whom it is she has so carelessly glanced at. And she, dashing herself on her knees, is there before Him in a moment, her outstretched arms seeking those feet she had been wont to clasp, this making His identity as certain as His resurrection. |

|

|

|

|

|

Such representations, and we find them reflected in the miniatures and other forms of art of the period, are worthy of the subject, but art, though about rapidly to advance in all material powers and beauties, was also about grievously to decline in the respect for the simplicity of Christian truth. This decline naturally coincides with that phase of the human mind which preceded the invention of printing, when the grand old traditions based on scripture began to be cast aside, and when scripture itself, which could alone refresh or replace them, was still a sealed book. It was a fatal time to such subjects as the Agony in the Garden, and the Appearance of Christ to the Magdalen, in which the infusion of human and puerile conceits led equally to offences to the eye and outrages to doctrine. Giotto’s scholars seem already to have lost the real meaning of this subject. Their imagination found in it nothing loftier than the fleeting fact of the Magdalen’s mistaking Christ for the gardener. All the pathos of her recognition, all the profound meaning of His identity, were lost; for in the place of Christ stands a figure shouldering a spade of a shovel – an evanescent oversight as presented to the eye of the weeping woman, a profane travesty as displayed to that of the Christian. . . . . Even the spiritually-minded Fra Angelico had his eyes ‘holden’ here, so that he neither saw the importance of preserving the Lord’s identity, nor the miserable absurdity of commemorating the momentary mistake of a tear-clouded eye. He also makes Christ shouldering a great spade, strangely incongruous with the glory that half conceals it. It was time now that pictures ceased to be the ‘books of the simple,’ when all they taught, in such a subject as this, was that souls returned to the body with a shovel over their shoulders. |

|

|

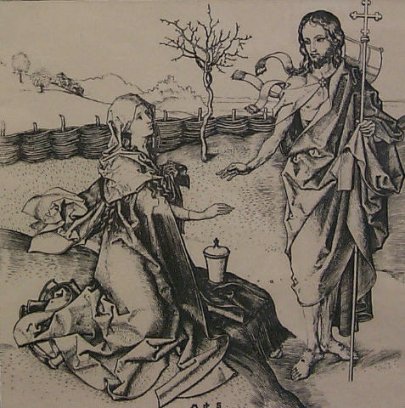

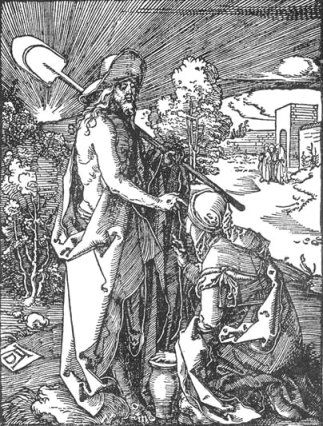

This innovation travelled slowly to the North. Martin Schon, (Schongauer) in the fifteenth century, gives the same Christ whom he has entombed in his previous plate, only with a rich robe and the banner of glory. Albert Durer, in the beginning of the 16th century, seems to halt between the two opinions, and tries to serve both Wisdom and folly, putting the standard of victory in one hand, and a spade in the other. Yet there have been writers on art, and no common ones, who have approved this wretched conceit.. . . . . ' |

|

|

|

|

|

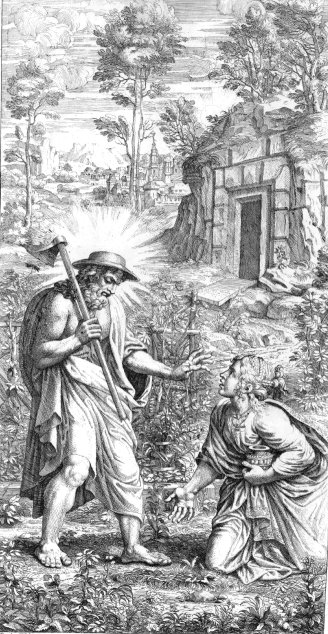

As stated before, in subjects of Christian art, where the actor and spectator are under different conditions, which they almost always are, there must be two different views. But art can choose but one of them, and is bound to prefer that which addresses itself to the spectator. Thus the rich mantle, and the standard of victory, even the nimbus of the Saviour, are not intended for the Magdalene’s eyes. She knows Christ by His familiar personal identity; we know Him by his divine attributes. Without them the story is not told, as art should tell it, so that those who run may read. Like all false ideas in art, this soon expanded into full-blown absurdity. No painter seems to have been able to resist the seductions of going wrong; the mine of false ore was diligently worked out. Raphael himself led the van – if, indeed, the design ascribed to him be his – with a figure, old and clumsy, with disorderly beard and plebeian face, wearing a broad-rimmed hat, and with a pick-axe on his shoulder. The light that encircles this figure is utterly incongruous, and the marks of the wounds on hands and feet profane. But for these, He would look like some Mercury or Apollo, veiling his beams beneath a crafty disguise, in order to beguile the rather light-looking lady at his feet. Poussin equally bowed the knee to false gods in this respect. With a consistency in error worthy of a better cause, Christ is made digging up carrots, which lie strewn on the ground before Him, His foot on the haft of the spade, Such designs would be better withdrawn from the series of the Passion, and renamed as ‘tableaux de genre’, fitting any story to them that might suggest itself, for it is almost needless to say, that the Magdalene is as little honoured here as her master. If the painter’s object is the embodiment of a momentary blunder, how come she is consenting to it? For every child who has read the story knows that this is not the person she turned to, recognised, and adored. |

|

|

|

|

|

My Comments In view of Mrs Jameson's opinions, it's probably just as well she didn't see this painting by Jan Breughel the younger - or at, least, I assume she never did. |

|

|

|

|

|

Never mind Poussin's carrots - Brueghel gives us a Christ who has produced an entire allotment of vegetables, and has clearly been busy loading up a cart ready to take them off to market. Even given that Flemish artists could never

resist painting their fruit and veg., this is rather over the top. But

do we go along with Mrs Jameson's thesis? I would

agree, though, that the idea did get a little out of hand. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Passion index | |