|

Another episode – or

sequence of episodes – in which differences between the four gospels

causes confusion. There are

also wider issues, discussed in detail in my regular guide to such

things, The Passion by Geza

Vermes.

As with all the Passion

events, John’s gospel moves the arrest and trial a day early, so

Christ himself becomes the sacrificial paschal lamb.

This leads to discussions about whether the various meetings and

trials could have in fact taken place at this time under Jewish law.

The other major issue is to what extent the Gentile–focussed

gospels ‘spin’ the story to incriminate the Jewish Sanhedrin and let

Pilate off the hook. In particular, that part of the narrative where the

crowd is offered the choice of Christ or Barabbas is regarded as

suspect. No such tradition is mentioned by historians such as Josephus,

and he should know. even Matthew’s gospel, considered the

one aimed at a Jewish audience, includes the scene of Pilate washing his

hands, declaring himself ‘innocent

of the blood of this just person’. Matthew does his best to implicate

all of the Jewish people: 'Then answered all the people, and said,

His blood be on us, and on our children.' ("7 v 25).

The portrait offered of Pilate by the gospel writers as a

reasonable but irresolute official is also at completely at odds with

the reality described by authors such as the ever reliable Josephus (Jewish

War and Jewish Antiquities) and Philo (Embassy

to Gaius). Pilate was quite clearly a brutal and vindictive thug who

ended up being recalled to Rome to answer for his cruelty and

incompetence.

So a quick outline of the

main events, then a look at the differing details of each gospel.

Christ is arrested, and

brought before the high priest, who declares him guilty. He is beaten. Peter,

who has followed Christ, now denies knowledge of him.

The next morning Christ

appears before the council of elders and priests, the Sanhedrin, where

his guilt is confirmed. He is then taken to Pilate, who does not find

fault in him. However, pressure from the Sanhedrin changes his mind and

he offers the crowd the choice of Christ or Barabbas. Barabbas is

chosen.

Mark

In Mark, the priests,

elders, and scribes are already assembled at the house of the unnamed

high priest. Various

witnesses are brought forward, some ‘false’. Christ is

asked ‘Art thou the

Christ, the Son of the Blessed?’ His

incriminating reply is ‘I am: and ye shall see the Son of man sitting

on the right hand of power, and coming in the clouds of heaven.’

The high priest rents his

clothes and Christ is

‘buffeted’. The narrative continues as above.

Matthew

Matthew names the high priest as Caiaphas. This gospel includes

verses on the repentance and remorse of Judas.

Matthew includes two

details relating to Pilate. One is the washing of hands, mentioned

already. The other is the unsuccessful intervention on Christ’s behalf

by Pilate’s wife. She became, in legend, the Christian saint and

Martyr Saint Procula. (She has other names.)

Luke

In Luke, when Pilate

realises Christ is a Gallilean he sends him to King Herod. Herod hopes

to see miracles enacted, but Christ does not oblige – he is mocked and

returned to Pilate.

John

First, Christ is taken to the priest Annas, father-in-law of Caiaphas,

before being taken to the high priest himself. As

the cock crows, Christ is taken to Pilate , but the priests do not enter

the judgment chamber ‘, lest they should be defiled; but that they

might eat the Passover’.

The trial before Pilate,

with its discussion of the nature of kingship, is far lengthier in John.

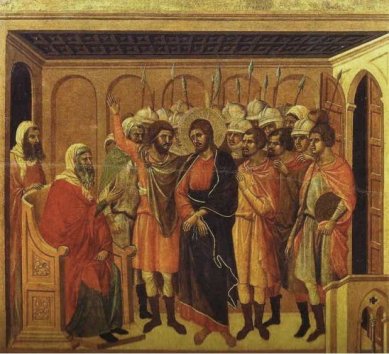

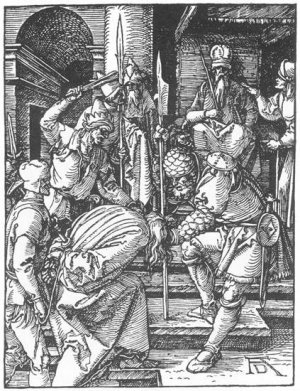

The trials in art

By far the most comprehensive guides are the Maesta of Duccio and the

'Small Passion' woodcuts of Durer. Let's start with their

interpretations of Christ before Annas.

Duccio shows the moment when Christ is found guilty; Durer illustrates

the subsequent beating.

|