|

The

Crucifixion |

|

| Let's cross the Alps, and head for Germany - and England. |

|

|

|

|

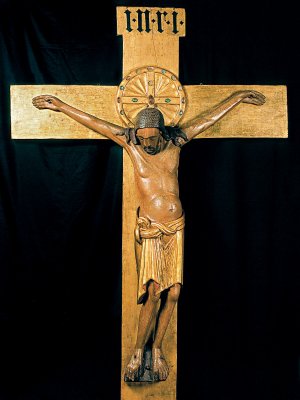

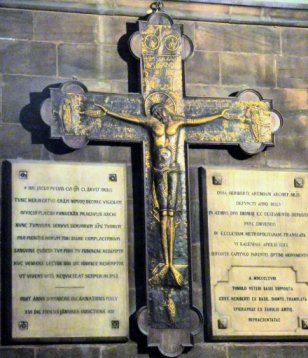

| Both of these

images are clearly Patiens, with the dead, slumped Christ with closed

eyes. The weeping figure on the manuscript page adds to the pathos. So

what are they? The manuscript page come from the Ramsay Psalter, a work probably from Winchester, dating from around 950. the crucifix, possibly the earliest surviving in Europe, is known as the Gero Cross, and is in Cologne cathedral. it dates from c 965 - 970. It is one of the greatest masterpieces of Ottonian art. Work, of the Ottonian school, in particular manuscript illumination, had a powerful influence in England. So these artworks date from around three hundred years before the Giunta Pisano and Cimabue crucifixes which are often lauded as the beginnings of Christus Patiens in Italy. So where does the image come from? It seems to me that it is all too easy to compartmentalise art: 'Byzantine', 'Carolingian', and so on. Medieval artists moved around far more than we imagine, much to the annoyance of art historians who prefer things to be cut and dried. Charlemagne was highly impressed with Ravenna and its art, and there are reports of Byzantine artists working in Carolingian Germany in the early tenth century. Carolingian artists worked in Milan in the early years of the ninth century, creating the Saint Ambrose altar. During the periods of iconoclasm in the eighth and ninth centuries, many Byzantine artists moved to Italy. In her excellent paper The Influence of Byzantine art in the West, * Helen Papastavrou discusses this at length. Apart from travelling artists, pilgrims and monks carried ideas in both directions. It would seem that, for centuries, the two ways of portraying Christ on the cross existed side by side. Below is the eleventh century Cross of Ariberto, in Milan, which clearly has elements of the suffering Christ. It is generally (and rather vaguely) described as having 'Byzantine influences'. Perhaps those influences were actually Carolingian. |

|

|

|

|

| While the monks of Winchester were busy working away on their illuminated manuscripts, just seventeen miles away the Benedictine Nunnery at Romsey was under construction. Two extraordinary survivals of that early church are a crucifix and a crucifixion scene. The crucifix, now on an outside wall, dates from around 1000. The scene, in a chapel inside the abbey, shows angels above, the Virgin and St John, and the soldiers with the lance and the sponge. The cross is sprouting tendrils - it has become the Tree of Life. This dates from c967, and is the earliest example in England. Clearly all is Triumphans here. Now let's head a little further into deepest Hampshire, to the beautiful Saxon church at Breamore, which has a rare surviving Saxon rood. It is in a poor state, but is quite clearly a suffering Christ. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

So where do we go from here? One approach is to consider whether the two strands we have been looking are derived from the two distinct theologies in early Christianity, one stressing the humanity of Christ and the other the spirituality - Christ as God. I've looked at this to some extent when looking at the earliest Crucifixion images. While in the Catholic church Arianism and such heresies had been largely dealt with, in the East it took longer. Arianism holds that Christ was created by God, but was not equal to him, and therefore would suffer as a human. Opposing theologies, such as Docetism, suggested that Christ was entirely divine and only had the semblance of a human being, so did not actually suffer. In the west, unorthodox ideas still emerged. Charlemagne, for example, was intrigued by the theory of Adoptionism. This suggested that Christ was a human being that had been 'adopted' by God. A little after his time, the Influential Abbot Paschasius Radbertus (785-865) I wonder, though, if the change was in sensibility rather than theology. The early Middle Ages was a time of flux. New religious orders were coming along with a much more austere lifestyle. There was a reform of the papacy. The writings of Anselm, in particular his Cur Deus Homo, stressed the necessity of Christ's suffering if human atonement was to be delivered. The Eucharist became more focussed on the idea of sacrifice, represented by Christus Patiens images above and behind altars. Triumphans was losing it's appeal. As well as this, there are two other considerations that need to be taken into account, one historical, and one artistic. The historical events were the capture of Jerusalem by Saladin in 1187 and the sacking of the city in 1244: triumph turned to suffering for Jerusalem Christians. Might this be reflected in Crucifixion images? In art, scenes of the Resurrection were rare until the late thirteenth century; after all there was no Biblical description to go on. Once they began to appear, the Crucifixion narrative altered; The Resurrection was now the moment of triumph, not the Crucifixion. |

|

| So what about the Franciscan

connection? A possible answer can be found in a seminal paper by Kurt Weitzmann, Thirteenth century Crusader Icons on Mount Sinai. (The Art Bulletin, Vol. 45, No. 3 September 1963.) Weitzmann discusses the complex situation relating to art in the Middle East at the time of the Crusades, and in particular the art produced in the City of Acre in the thirteenth century, following the fall of Jerusalem in 1244. Here icons were produced in large numbers. Some artists were from the Byzantine tradition, but others came from Italy and France. The Franciscans were here too. It was from this extraordinary melting-pot that works of art such as the icon from St Catherine's on the previous page emerged, and, maybe also a tradition that would last for centuries. For Franciscans, the suffering Christ was the perfect model for their own founder, and for the way they lived their lives. In the early thirteenth century the Franciscans embraced the Patiens image and made it their own. |

|

* from Byzantium: an Oecumenical Empire. Exhibition catalogue, Byzantine and Christian Museum, Athens, 2002. |

|