|

The

Crucifixion |

|

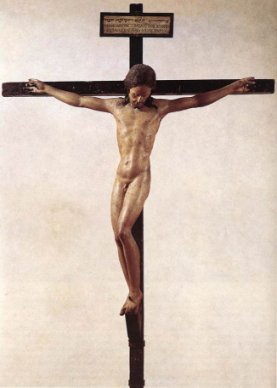

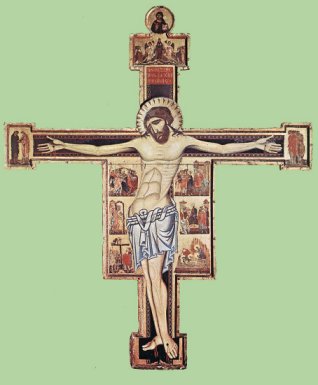

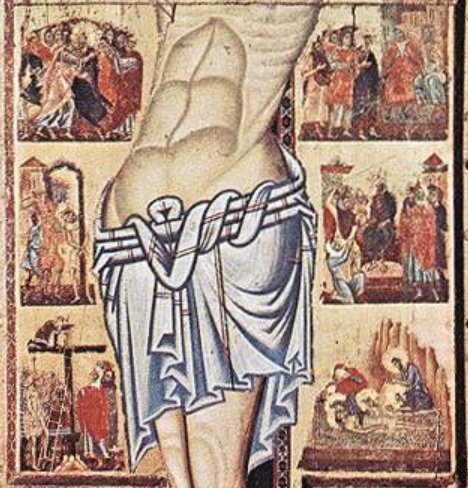

| The strict definition of a crucifix is a three dimensional representation of Christ on the Cross, such as the one by Michelangelo below left. By and large this definition is ignored. A crucifixion scene such as some of those I've looked at are clearly not crucifixes. And yet - what about the work by Coppo di Marcovaldo below left? It is certainly called a crucifix, and yet it includes a series of pictures of the Passion events, as can be seen on the detail below. | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

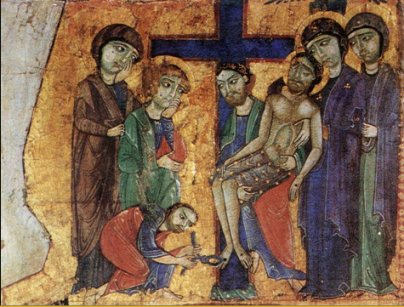

| Technically, this is a historiated cross or crucifix, a cross that includes painted narratives. Here is another, from the Uffizi, with a detail of one of the scenes - the deposition. | |

|

|

|

| In later crucifixes the stories disappeared, though many did include characters such as the Virgin and John. | |

|

|

|

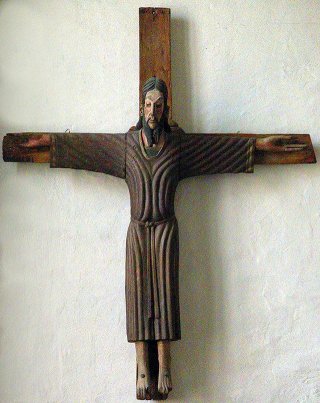

| The

Volto Santo of Lucca This crucifix, in the Cathedra of San Martino in Lucca, has a delightful legend as to its origin. It is said to be a copy of an original carved by Niocodemus, who assisted Joseph of Arimathea in the deposition from the cross. It supposedly arrived in Lucca in 742; pilgrims helped themselves to bits of it, thus necessitating this copy. It became the model for other early wooden crucifixes. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The

function of the crucifix A question we cannot shy away from - what is the crucifix for? Are we not meant to be suspicious of graven images? The answer, I believe, is that the crucifix was not, and is not, an object to be worshipped, but a means to focus prayer. Richard Viladesau in his excellent book The Beauty of the Cross describes the change that took place in the monastic spiritual life in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the time when the crucifix was becoming an established feature of churches and chapels. He describes the change from a concern about the 'Lordship of Christ', demonstrated in the Resurrection and Ascension, to a greater appreciation of Christ's humanity, demonstrated by his suffering on the cross. The writings of St Anselm in were hugely influential, particularly his prayers directed to Christ, and writings such as his Discourse on the Passion of the Lord, much of which is written in the second person, directly addressing Christ. The crucifix was there not just to be looked at, but to be spoken to as well. |

|