|

The Passion of Christ |

|

|

The Lamentation of Christ |

|

|

The events that took place between the Crucifixion and the Entombment of Christ are not described in any detail in the Gospels. Here's Matthew: When the even was come, there came a rich man of Arimathaea, named Joseph, who also himself was Jesus' disciple: He went to Pilate, and begged the body of Jesus. Then Pilate commanded the body to be delivered. And when Joseph had taken the body, he wrapped it in a clean linen cloth, And laid it in his own new tomb, which he had hewn out in the rock: and he rolled a great stone to the door of the sepulchre, and departed. (Chapter 27) John adds another character, Nicodemus: And there came also Nicodemus, which at the first came to Jesus by night, and brought a mixture of myrrh and aloes, about an hundred pound weight. (Ch 19 v39) John also gives a location for the entombment: Now in the place where he was crucified there was a garden; and in the garden a new sepulchre, wherein was never man yet laid. (v 41) The Virgin Mary is a central character in Lamentation scenes, but she is not in fact mentioned in this part of the narrative. John firmly places her at the Crucifixion, but not at the removal of the body to the tomb. Luke mentions the women of Galilee: 'And the women also, which came with him from Galilee, followed after, and beheld the sepulchre, and how his body was laid' (Ch 23 v 55) Mark specifies two Marys, Mary Magdalene and Mary the mother of Joses, who 'beheld where he was laid'. (Ch 15 v 47) Art curators love to put their art into tidy categories, but that doesn't always work here. The Lamentation of Christ can form part of a Deposition scene, or of the Entombment. Who is there? The Virgin Mary is the central character. Alongside her will be St John and Mary Magdalene. Joseph of Arimathea will sometimes appear, and Nicodemus, who can be recognised by his container for the Myrrh and Aloes. Other women may represent the women of Galilee or the various other Marys. Occasionally, anachronistic figures such as saints are included. The Lamentation in Art Some versions of the Lamentation scene are called 'Pieta' and I'll look at these on the next page. The usual Lamentation scene with a group of character surrounding the body of Christ has been a familiar image since the early Renaissance. At this point I am tempted to say 'here's Giotto - nothing can compare with this, so why bother with anything else?' |

|

|

|

|

|

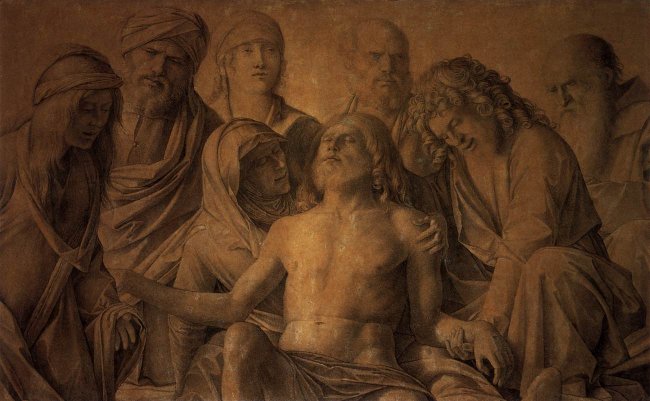

Never before in art had there been such a powerful depiction of grief. It's hard to tear ones eyes away from this, but we had better look at some other versions! The Version by Fra Angelico from San Marco, Florence (below left) is an extraordinary contrast to the Giotto: here the mourner's grief is contained, yet somehow equally powerful, perhaps appropriate for its context as an object of contemplation in a monk's cell. The standing figure is St Peter Martyr. This fresco also includes the tomb of Christ in the background. There is a well-known Lamentation by Bellini in the Accademia in Venice, but I'm going for this chiaroscuro painting from the Uffizi. As with the Fra Angelico, the grief is understated, but the feelings of the mourners is clear. Look at the compassion in the face of the turbaned man to the left. |

|

|

|

|

|

Now here's one that doesn't quite work for me, and

one that really does. The one on the left is by Joos van Cleve and

is in the Louvre. There are various quite interesting things going on in

the rather splendid background, but the mourners here make for a rather

ill-assorted bunch. The rather smug looking figures right and left are

presumably the donors, and to me they are rather intrusive. The martyred

saint, (Peter again?) is showing more interest in the male donor than the

grief of Mary. The praying female figure at the back on the left simply

looks bored, and Mary Magdalene's gesture suggests nothing worse than if

she had dropped something on the floor or spotted a mouse. The Mantegna on the right is worlds away, and was top of the list of things I wanted to see when we went to the Brera in Milan in 2013. Yes, it's a stunning ,masterpiece of perspective, but just look at the grieving faces, only just glimpsed on the left, almost as if they were struggling to push themselves into the picture. It's a picture that haunts you, and, legend has it, Mantegna saved it up for his his own funeral. |

|

|

|

|

|

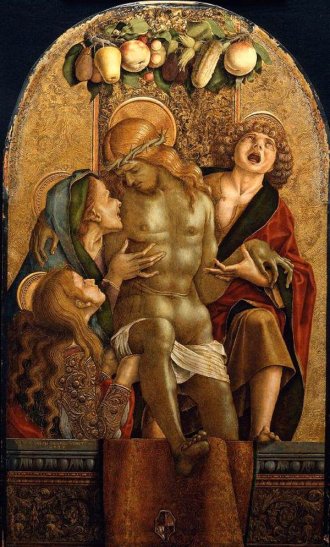

Let's make room for a couple of eccentric

versions. Crivelli was a master of the exaggerated form, sometimes

to point of distortion. The Virgin's face here does look a little odd,

while John looks as if something very heavy has fallen on his foot. The

symbolic fruit and nuts in Crivelli's paintings always provide interesting

material for those who enjoy interpreting such things, though I do wonder

if that pear isn't fixed to the branch at the wrong end. However, the

Magdalen is rather beautifully done. The version by Geertgen tot Sint Jans Has some very unusual features. Prominent behind the mourners we see the Bad Thief being tipped down a hole, on his way, presumably, to Hell. the Good Thief hasn't been dealt with yet. A dog looks on, perhaps attracted by all the bones. A group of soldiers are putting the world to rights at the top of the hill. Around the dead Christ are the usual Marys, all with Geerten's typical egg-shaped heads. The group to the right are a puzzle. The curly-haired St John sits in the middle, but who are the other characters, particularly the bearded one? The elderly man scratching his head might be Joseph of Arimathea. Behind him, surely, is Nicodemus, identifiable by the shroud he is carrying and the spice jar behind him, outside the tomb. But what of the other two? They seem far to involved in the event to be donors, and, in any case, the portraits are hardly flattering, though the bearded man's had is splendid. Looking through Geertgen's work, he does seem keen on beards - a similar looking character can often be identified. Another interpretation would be that he is Joseph of Arimathea - after all, he is identified as a wealthy man, and his fur lined clothes fit that description. So what about the cloaked figure behind him? The work was painted for the monastery of the Knights of St John in Haarlem; perhaps this figure represents a member of that order? |

|

|

|

|