|

The Passion of Christ |

|

|

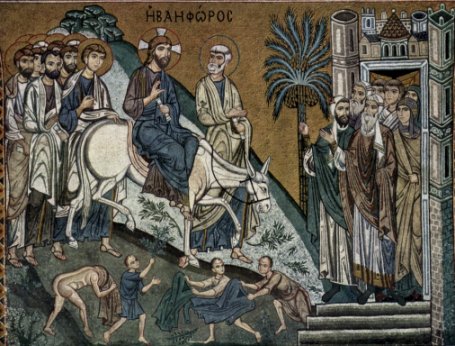

The Entry into Jerusalem |

|

|

|

|

|

Chapter 21 of Matthew's gospel describes this event

thus: And when they drew nigh unto Jerusalem, and were come to Bethphage, unto the mount of Olives, then sent Jesus two disciples, Saying unto them, Go into the village over against you, and straightway ye shall find an ass tied, and a colt with her: loose them, and bring them unto me. And if any man say ought unto you, ye shall say, The Lord hath need of them; and straightway he will send them. All this was done, that it might be fulfilled which was spoken by the prophet, saying, Tell ye the daughter of Zion, Behold, thy King cometh unto thee, meek, and sitting upon an ass, and a colt the foal of an ass. And the disciples went, and did as Jesus commanded them, and brought the ass, and the colt, and put on them their clothes, and they set him thereon. And a very great multitude spread their garments in the way; others cut down branches from the trees, and strawed them in the way. And the multitudes that went before, and that followed, cried, saying, Hosanna to the Son of David: Blessed is he that cometh in the name of the Lord; Hosanna in the highest. And when he was come into Jerusalem, all the city was moved, saying, Who is this? And the multitude said, This is Jesus the prophet of Nazareth of Galilee. The event is seen by the author of Matthew as the fulfilment of a prophecy from Zechariah: Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion; shout, O daughter of Jerusalem: behold, thy King cometh unto thee: he is just, and having salvation; lowly, and riding upon an ass, and upon a colt the foal of an ass. Ch 9 v 9:9 There are other earlier echoes: From the Apocrypha, for example: And they entered into it the three and twentieth day of the second month, in the year one hundred and seventy-one, with thanksgiving, and branches of palm trees, and harps, and cymbals, and psalteries, and hymns, and canticles, because the great enemy was destroyed out of Israel. 1. Maccabees 13/51 And from Isaiah: Go through, go through the gates; prepare ye the way of the people; cast up, cast up the highway, gather out the stones; lift up a standard for the people. Behold, the lord hath proclaimed unto the end of the world, say ye to the daughter of Zion, behold, thy salvation cometh, behold his reward is with him, and his work before him. 62 v 10-11 There are three views on the veracity of the biblical accounts. A straight-forward traditional view would be that yes, the prophecy was fulfilled. Some scholars contend that Christ and his associates deliberately orchestrated the event to resonate with the early tradition. A more sceptical suggestion is that Matthew spun the story to match the OT references - it may not have really happened that way at all. |

|

|

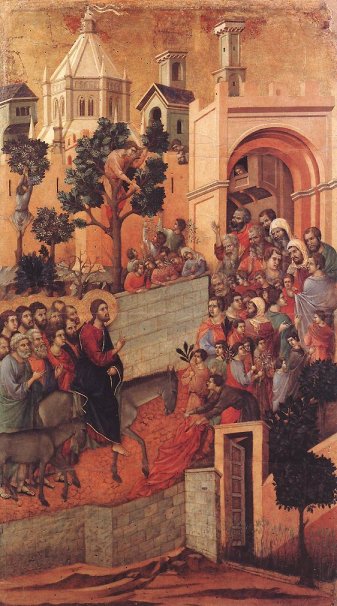

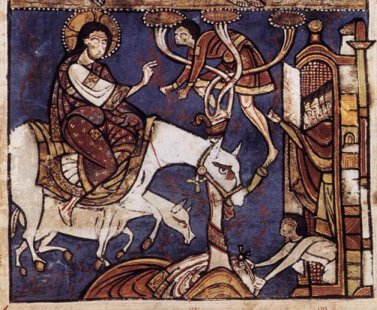

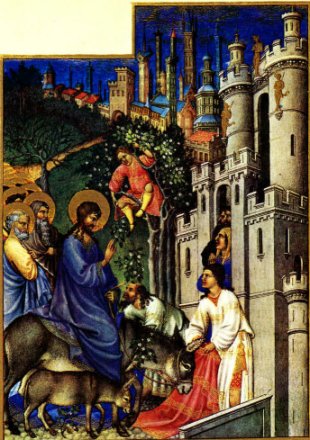

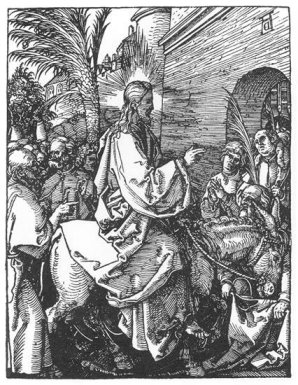

One colt or two? Over the century scholars have agonised over one aspect of Matthew; how could Christ have ridden on two asses at once? There is no such problem in the other gospels: 'And they brought the colt to Jesus, and cast their garments on him; and he sat upon him.' (Mark) 'And they brought him to Jesus: and they cast their garments upon the colt, and they set Jesus thereon.' (Luke) 'And Jesus, when he had found a young ass, sat thereon; as it is written, Fear not, daughter of Zion: behold, thy King cometh, sitting on an ass's colt.' (John). Note John's direct reference to Zechariah. The general view is that Matthew simply misread Zachariah's 'an ass, and upon a colt the foal of an ass'. It's actually the same animal. This is simply a Hebrew rhetorical device - 'he met a man, and a very fine man too'. Only one man is intended. Early artists were equally confused. Duccio (above) has two animals, as have these. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Why

a colt? The texts refer to colts, asses, and donkeys. An ass and a donkey is (I believe) the same animal; Equus Asinus. (Please correct me if I am wrong). A colt usually refers to a male horse under four years old. In this case the reference is almost certainly to a young donkey. There are, it seems, ritualistic reasons why a young, unridden animal is needed - it has been set aside for this sacred task. The modern feeling about the donkey ride is that this is sign of Christ's humility - 'lowly, and riding on an ass' as Isaiah has it. Not all scholars see it this way, and the quote from Maccabees refers to a triumphant army entering Jerusalem. People arriving at the Passover were meant to come on foot; riding was reserved for kings and the like. Rather than being lowly, riding into Jerusalem stresses Christ's role as Messiah and liberator. Some images aren't very donkey-like, but Giotto certainly knew a donkey when he saw one. Durer's is O.K., but it's no match for Giotto. |

|

|

|

|

| It is interesting that all the images so far show the movement of the painting from left to right. This is the natural way for viewers used to the western tradition of writing going from left to right: that's how we scan a painting. This picture by Rubens just seems wrong somehow - Christ seems to be heading away from Jerusalem. Or is it just me? | |

|

|

|

|

Clothing The first reference to clothing tells us that the disciples put their clothing on the colt for Christ to sit on. This seems an odd detail, but it emphasises that the animal is not yet broken in and therefore would have no saddle. The second reference describes the populace taking off their clothes and spreading them before Christ. In this mosaic from the Palatine chapel in Palermo one of the multitude seems to be taking things just a little too far. This might raise sniggers to a modern audience - but I wonder, is this notion of the multitude taking off their clothes a counterpoint to later events, when Christ himself is stripped before being crucified? This element of the story is particularly meaningful to Franciscans, echoing as it does the incident in which Francis handed his clothes back to his father. |

|

|

|

|

|

Finally, a very eccentric version indeed. |

|

|

|

|

|

The setting is the village of Cookham, and

the locals are pushing their way through their cabbages to get a better

look. Outrageous? Well, look again at Duccio's version at the top of the

page. Gothic windows in first century Jerusalem? |

|