|

'And they come to Jerusalem: and Jesus went into

the temple, and began to cast out them that sold and bought in the

temple, and overthrew the tables of the moneychangers, and the seats of

them that sold doves; And would not suffer that any man should carry any

vessel through the temple. And he taught, saying unto them, Is it not

written, My house shall be called of all nations the house of prayer?

but ye have made it a den of thieves. And the scribes and chief priests

heard it, and sought how they might destroy him: for they feared him,

because all the people was astonished at his doctrine.' Mark 11

15- 18

As with the anointing of Jesus, there are chronological

issues with this story. The synoptics make it a part of the events of

the Passion, following the entry into Jerusalem, but John has a

temple cleansing story set very early in Christ's ministry. Some say

John simply misplaced the story; others say that there were two separate

incidents. Bart Ehrman, in Jesus Interrupted, takes the former

view; He suggests, reasonably enough, that a young Jesus would hardly get

away without being arrested for such an action.

I think there are other reasons for placing the single event in

the week of the Passion.

* It beefs up the narrative and gives the high priests

another good reason to 'destroy him'.

* Had he done it before, the Synoptics would surely have mentioned

it.

* John's account does include significant details also included

in the Synoptics - the pigeon sellers, for example; and does refer to

the passion events to come.

The modern take on the story is that Jesus discovered,

within the temple, a cross between a local market and an airport

currency exchange; as if St Peter's in Rome had set aside a chapel for Prada,

Gucci, and so on, to open branches for tourists. This isn't the

case. The sellers of pigeons and lambs were providing animals for

the Passover sacrifice; the visitors to Jerusalem could hardly bring

them with them. And the currency exchange allowed people to change their

own, perhaps Roman currency, into special, sacred coins that could be

used to purchase the animals, or make donations to the temple for upkeep.

All

perfectly above board, and in fact a requirement for Jewish observance

as laid out in the Torah. No more reprehensible, then, than an English cathedral asking

for a donation at the door or running a tea shop.

Theological speculations are many and various and I'm certainly

not going in to them all here. The most common view is that the High

Priests had 'sold out' to the Romans and Jesus wanted to metaphorically

rebuild the temple, or perhaps return Jewish worship to its roots, and

the cleansing was a form of enacted parable. Such a parable would also

prefigure the forthcoming apocalypse of which he preached. Another less exalted view was that the authorities were on the fiddle,

keeping the money rather than making good use of it. None of these

theories explain why the poor old traders had to take the rap.

As with all Passion events, there are references to Old Testament

prophecies, in particular Isaiah Ch 56 6 - 7 and Jeremiah Ch 7 v1,

though some scholars feel these are rather forced. Perhaps more

interesting is the account of the triumphal recapture of Jerusalem

by the Maccabbees in 164 BC, which was followed by a cleansing and

rededication of the temple. This is recounted by Josephus in Antiquities

of the Jews and in the OT apocrypha (1 Maccabees ch 4.) The

parallels would hardly be lost on the history-conscious Jews of the

time, and reinforces the idea of Christ as Messiah and liberator.

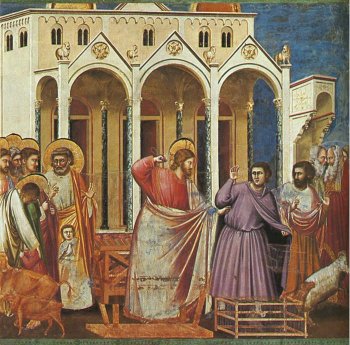

This event is rarely found in early art; sadly, Duccio did not

include it in his Maesta. Giotto's fresco in the Scrovegni Chapel, Padua,

is the only pre-fifteenth century example I've located. So why here?

Change 'moneychangers' to 'moneylenders' and suddenly there is a

relevance. Enrico Scrovegni built this 'new temple' to redeem the soul

of his dead father Rinaldo, the notorious usurer.

|