|

The

Crucifixion |

|

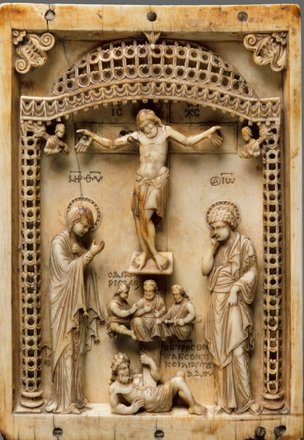

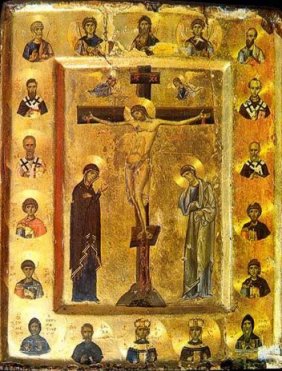

| There is a widely held view

that the move away from images of the triumphant Christ to those of the suffering Christ was entirely inspired by

Byzantine art, and was brought back to Italy by the Franciscans as

a result of the crusades. I want to the explore this

change in detail here, and consider whether this view is somewhat

simplistic. Let's begin by looking at examples of both types of image and exploring the differences. |

|

|

|

|

|

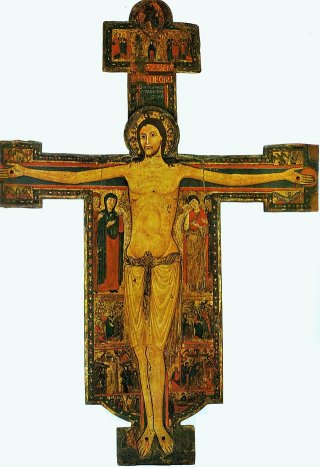

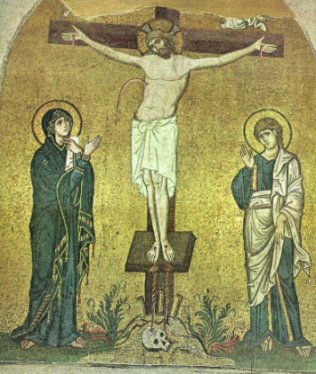

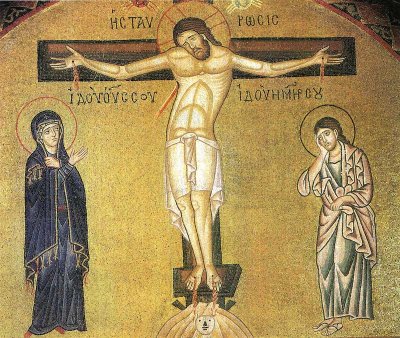

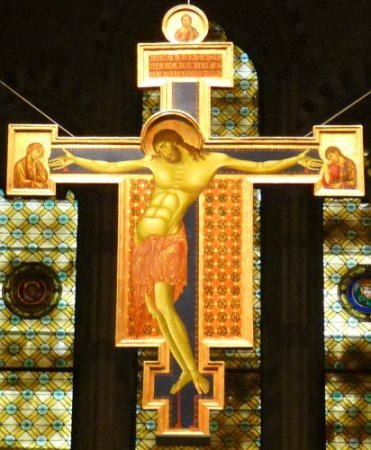

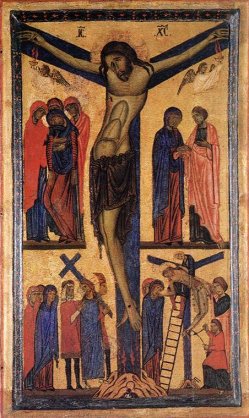

So, Triumphans: Christ

is alive, head upright, eyes open, no sign of suffering. Patiens: the

dead Christ, eyes closed, body slumped and twisted, an almost

transparent loin cloth, clear signs of suffering. |

|

|

|

|

| Some more Byzantine images: | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

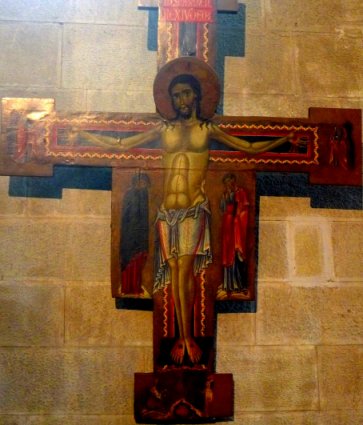

Let's look again at some further examples of Italian Christus triumphans crucifxes: |

|

|

|

|

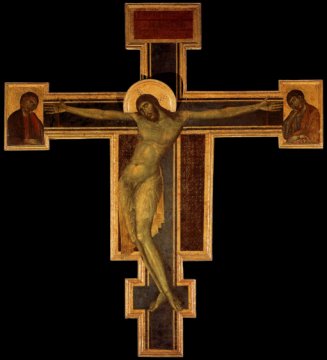

And Christus Patiens, from the late thirteenth century onwards: |

|

|

|

|

| These examples

demonstrate that that the change didn't entirely convince everyone in

Italy. The

Margarito crucifix has a similar date to the Cimabue, and the two pieces

are less than half a mile from each other. Margarito must have known the

Cimabue, but the style wasn't for him, or the commissioners of his

crucifix. Note too the difference in the loincloth between the two

works by Cimabue. It could be that for the Dominicans of Arezzo,

transparency was a step too far, though it was clearly what the

Franciscans of Florence wanted. So, all cut and dried then. The Franciscans that went with the crusaders in the twelfth century sought out the mystical, emotional side of Byzantine art, perhaps from monasteries, and introduced the idea to Italy where it flourished from the mid thirteenth century onwards. If only life was that simple. |

|

*Images of Power and the Power of Images: Control, Ownership, and the Public Space 2012 |

|